This paper aims at highlighting a few high-level points relative to the Open Innovation Model, although today the literature about Open Innovation is abundant. NineSigma was one of the first companies offering Open Innovation services. Needless to say, NineSigma contributed to shaping that industry.

This paper will walk you through:

- BRIEF HISTORY

- HIGH-LEVEL MODEL

- OPEN INNOVATION VS. CLOSED INNOVATION

- TYPICAL PROCESS

- KEY SUCCESS FACTORS

- GOING FORWARD

Brief History

Before even using the words “Open Innovation”, most companies had already embarked on activities that would be named later that way. If we loosely define Open Innovation as innovating with partners, companies have always practiced it by working closely with partners from their close networks: suppliers, selected customers, privileged universities and research labs. Some may have organized innovation competitions, while others have hired organizations (start-ups for instance) to help develop their research or product development work. Corporations also build their strengths on their employees’ capacity and intelligence to help grow and innovate the business. Researchers, technologists and scientists in most organizations often connect with peers, whether internally or externally, to discuss and get more insights on problems they try to solve.

Some corporations quite early on identified the potential to dramatically increase their innovation portfolio by tapping into a vast, global community of innovators, start-ups, small and medium-sized companies, large ones, universities, labs in a more systematic, methodological way. One of the emblematic examples was Procter & Gamble. Late 1990s P&G’s management team grasped the value proposition behind what was to become known as Open Innovation. They implemented it into their innovation strategy through what has been called ‘Connect + Develop’. This initiative was to become a successful program for fostering collaborations with innovators from outside the company’s four walls.

In 2003, Harvard Professor Henry W. Chesbrough coined the term ‘Open Innovation’ in a seminal book[1]. His research work led him to define Open Innovation as the use of: “purposeful inflows and outflows of knowledge to accelerate innovation internally while also expanding the markets for the external use of innovation”.

Open Innovation as described by Chesbrough aims at increasing the circulation of knowledge, especially with from players outside the organization, and at integrating this flow of information into the organization’s innovation processes.

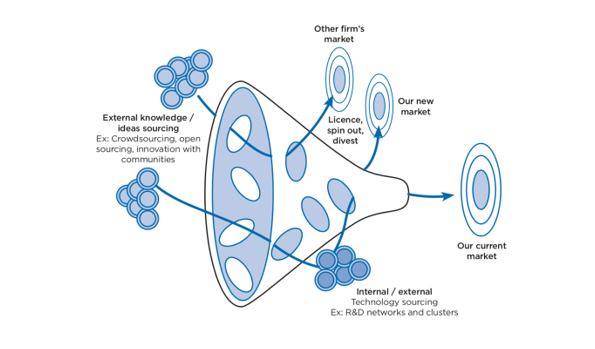

The Innovation Funnel Model[2]

High-Level Model

Open innovation primarily includes ‘outside-in’ approaches, where external ideas and technologies are brought into the organizations innovation processes, and to some extent, ‘inside-out’ approaches, where un- or under-utilized ideas and technologies go outside to be incorporated into other organizations’ innovation processes.

A typical example of an outside-in Open Innovation project managed by NineSigma:

“PepsiCo needed to find a way to reduce the amount of sodium in its potato chips without reducing the salty flavor that customers love. Its search — despite looking across the entire food industry and not only the snack industry — had not produced a viable solution. So we [NineSigma, an Open Innovation consulting company] helped express the need and craft a technical brief in a way that cast a wider net. That brief, Nanoparticle Halide Salt: Formulation and Delivery, was then “marketed” to a broad audience of technical experts. Proposals came in from a variety of industries and organization types, including energy and fuels, pharma, and engineering services. The winning response to the brief came from the orthopedics department of a global research lab. The scientists there had developed a way to create nanoparticles of salt which they needed to conduct advanced research on osteoporosis. For PepsiCo, this wasn’t in itself the ultimate solution, but the search yielded a valuable new partner and perspective. It went on to solve its problem in a truly innovative way.”[3]

The main assumption behind the Open Innovation model is that by sourcing valuable ideas, innovations and solutions from outside the walls of an organization, it brings not only more brainpower to solve problems but also a different perspective that can unlock the comfort zone in which many companies reside by only working within their existing ecosystem. It is also a way to identify more options to choose from, and to increase the chances of finding one that has the potential to advance the future product beyond the competition’s capabilities.

Open Innovation vs. Closed Innovation

Open Innovation certainly contradicts the traditional way of running R&D and innovation activities in a corporation. These activities traditionally occur internally and build on the resources (human and financial) the organization can provide and allocate. R&D is focused on developing products and services that later would be launched commercially. This model of ‘Closed Innovation’ (as opposed to Open Innovation) relies on a certain number of assumptions as stated by Chesbrough, that companies must consider. They design, build and promote products on their own, based on their perception of the market. They must attract and secure the best talent possible to enable fruitful research and innovation work. They must build barriers to prevent competition from outpacing or ‘stealing’ from them, and these barriers usually take the form of strongly-enforced Intellectual Property (IP) through for instance patents.

But powerful forces, such as sustainability, digitalization, speed of change in customer demands, increased complexity of technologies, globalized innovation, are at work, impact business, disrupt the markets and force companies to transform and reinvent their growth model at a faster pace.

For instance, it gets less and less conceivable for a company to acquire all the resources, knowledge and expertise on every new technology that it may require for innovating. There is a pressing need to find ways to access in a more agile manner the expertise whenever needed. An Open Innovation model seems in line with the growth strategy companies rethink today.

Typical Process

Fundamentally, and if we stick to the outside-in model, it is a two-way game. On the one hand, Innovation Seekers (“Seeker”) want to find and connect with the most promising solutions and partners, and on the other, Solution Providers (“Provider”) have an opportunity to respond to real, tangible projects with their ideas and technologies.

Innovation Seekers tend to be large and global corporations or SMEs, mostly for issues that concern their innovation and product development roadmap, but also for larger challenges whose resolutions could help improve the world. It can also be NGOs, governmental bodies or public administrations willing to open up to broader audiences to tackle more global, societal challenges in search of solutions that could impact the life of large populations.

Solution Providers are typically inventors, start-ups, suppliers and customers, contract research organizations, research labs, universities, sometimes competitors and companies with complementary offerings to form joint ventures or any other arrangements.

A third stakeholder in this Open Innovation model can be companies, such as NineSigma, that can facilitate the process by working with Innovation Seekers to identify and articulate their needs, and by reaching out to a global community of Solution Providers in search for solutions.

Such ‘intermediaries’ as sometimes they are called can act as a third party to make the connection between a Seeker who wants to remain anonymous and a range of Providers intermediaries can access because they have built overtime global networks. For instance, NineSigma has reached out to over 2,5 million contacts since its inception, establishing more than 75,000 connections for 800 clients through 5,000 projects.

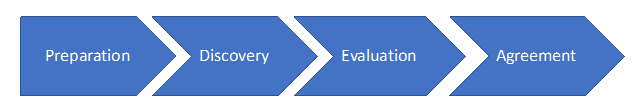

In general, the Open Innovation process can be summarized in four major phases: Preparation, Discovery, Evaluation and Agreement[4].

Preparation

“The Innovation Seeker’s objective is to select a need that has high strategic value, in an area in which she is free to engage in the solution space. These needs must be pre-qualified specifically for the Open Innovation arena in order to create a higher likelihood of success. During Preparation, the organization is making a commitment to a specified outcome (e.g. follow through, financial investment) against a set of established criteria, while also minimizing the risk of surprise IP restrictions once the project is underway.”

This phase is usually critical as it establishes the company’s Open Innovation journey to accelerate innovation. The Preparation phase focuses on identifying the key domain areas and needs (most of the times but not always, non-core areas are the ones to target first. Non-core areas do not mean less important, but rather these areas where there may be a lack of expertise or technology gaps or white spaces, quite fundamental to address in order to build new, compelling products) where finding and acquiring solutions from outside can make an impact on the business. Implementing an Open Innovation strategy today must be consistent with the business strategy.

Discovery

“The goal of the Discovery Phase is to identify a variety of high-quality potential solutions and partners that have the potential to provide the missing expertise, insight, technology, and capabilities to address the defined need. The Seeker compiles a portfolio of potential solutions that contribute value through their approach (e.g. alternative paths, sustainability, cost savings, breakthrough) to funnel into the Evaluation phase. The challenge during Discovery is how to maximize the quantity of high-quality information by tapping into the greatest breadth and variety of resources, without compromising IP.”

What is important in this phase is to actively tap into the right communities. There is no need to go too broad and receive hundreds of proposals that eventually will prove not to be relevant. As said before, it is critical to precisely define the problem upfront. This will dramatically help identify the parties both in related or non-related spaces that can bring new approaches and innovative solutions. It can be efficiently done through a combination of experience and knowledge of global technology and science networks.

Consider for instance the Ellen McArthur case

The Ellen McArthur Foundation (EMF) sought the help of NineSigma to organize an Innovation Challenge to find alternative materials that could be recycled or industrially composted. EMF was created in 2010 to speed up “the transition to the circular economy”.

The “Circular Materials Challenge” was scoped with EMF and leading brands committed to use 100% reusable, recyclable or compostable packaging by 2025 or earlier. Among those brands were Amcor, Ecover, Evian (Danone), L’Oréal, Mars, M&S, PepsiCo, The Coca-Cola Company, Unilever, Walmart and Werner & Mertz.

By going deep into science and technology networks, however with a precise brief, NineSigma identified 63 Responses from 23 Countries. EMF and the judging panel ranked the proposals and selected 13 for in-depth due diligence. The judging panel found it very difficult to select the winners given the quality of the shortlisted proposals.[5]

Evaluation

“The Seeker’s goal during the Evaluation Phase is to assess the funnel of potential solutions and partners against pre-established criteria, in order to identify a single or several vetted potential solutions. The selected solutions and partners represent the best path to address the stated need, and the parties have stated a mutual interest in forming a defined type of collaboration.”

This phase is where usually non-confidential information, yet sufficiently detailed, is carefully screened by the Seeker. Further clarifications can be requested to better understand a point or another. It is important to mention that in order to ensure a proper flow of information between the parties without compromising any of the parties’ trade secrets or IP, only non-confidential information is shared during the Discovery and Evaluation phases. There exists a non-confidential space where parties can interact and decide if it makes sense to go deeper in the relationship. If it does not happen, then none of the parties was put at risk and each one can go away without impact.

Agreement

“The Agreement Phase is the point when the Seeker and Provider make a mutual commitment to engage together in a collaboration or mutual exchange. This commitment may result in a series of collaboration agreements which begin with proof-of-concept, in a single joint development agreement that leads to commercialization, or in a single event that transfers IP or access to IP from the Provider to the Seeker. In all cases, the goal of the Agreement Phase is to define the relationship between the Seeker and the Provider such that the agreement outlines the shared obligations and mutual rewards that will engage both parties enthusiastically in the collaboration.”

The end goal of Open Innovation is to create meaningful collaborations, where each party can benefit from the other’s expertise, strengths and willingness to develop something in common. However, this phase is probably where oftentimes the Open Innovation effort enthusiastically embraced in the first place eventually fails.

Key Success Factors

This section highlights some of the key points to succeed with Open Innovation. Indeed, and even though Open Innovation has always been part of the way a company operates, through different modalities, there are still quite a lot of barriers that hinder Open Innovation from fully be embedded into an innovation strategy. Some of the points below draw some perspective on what to do.

Business Strategy

Innovation is at the core of the high-performing companies. In these companies, innovation is centralized in upper management — particularly with the CEO[6]. Innovation is part of the CEO’s agenda as for any initiative to deliver true value, the effort must clearly align with the company’s business strategy. Innovation is poised to be instrumental in the future growth of the company, provided there is a clear leadership in that direction.

This is why some of the most innovative companies bring people from the business strategy side of an organization into the innovation front-end from the start—at the ideation phase of any new, potential innovation. It may prove to be critical to making innovation pay off in the long term, rather than having it be a potentially losing proposition. That requires knocking down silos within a company. It means “looking horizontally” within the company and across the various industries. Which to a large extent is a matter of changing or even transforming the organization and its culture.

Culture

High-performing companies are the ones nurturing a culture of innovation across every business function, from R&D to HR, finance, sales, product, marketing, and more, according to the same survey from CB Insights.

In R&D functions alone, many companies still face the ‘Not-Invented-Here’ syndrome: “Just as biological organisms have antibodies whose job it is to combat intruding organisms, every company has human versions of antibodies who make it their business to fend off foreign ideas”[7].

Change is disruptive and challenges the status quo. This is why transforming an organization’s culture takes time and effort, and probably a group of motivated people with great leadership skills who are willing to make things happen.

Siemens has embraced an Open Innovation strategy that help instill an new innovation mindset.

A few years ago, the Corporate Innovation Team at Siemens realized it became strategically important to search for new solutions, technologies and partners beyond the traditional Siemens ecosystem. There was a need identified to accelerate the search for solutions on various and multiple technology challenges across all business units and business areas.

Siemens has defined a compelling innovation strategy to foster both internal and external collaborations. In order to develop external collaborations, various “value pools” have been defined: academia, research, universities, start-ups, companies outside the Siemens traditional ecosystem, individuals with skills in digital, algorithm… Several initiatives have been launched to facilitate interaction with these “value pools”, such as hackathon, co-creation, accelerator, scouting activities…

One major initiative in this strategy is the “Open Call for Suppliers”, which resides on NineSights, NineSigma’s Digital Innovation Platform, as a “Siemens Gallery”. This initiative has become a central piece of the Supply chain management to identify new partners and make Siemens more efficient.

Most important perhaps, the internal community of Open Innovation promoters at Siemens has literally grown from a few people to more than 2,000. This community grows every day and helps change the cultural mindset from “The lab is our world” to “The world is our lab”.

The effort has so far brought in great amount of efficiencies, in terms of time and money, while accelerating time to market of many solutions.

Organization

Organizations (i.e. Seekers) starting or already engaging in Open Innovation often think that they should focus most of their effort on the external outreach aspects, that is, on deploying teams to go out there and scout the world. But to be successful at Open Innovation, organizations need to prepare for managing the entire process including the critical part, i.e. internalizing the findings. Why? Because fundamentally organizations underestimate the effort it requires to internalize new approaches, to develop solutions from technologies they do not master, to build strong and meaningful relationships with new partners. Large corporations have also to cope with their ‘Big Corporate Time’, sometimes slowing down processes or caught by the day-to-day business, thus leaving hardly no room for new initiatives.

This is why any corporation engaging in Open Innovation must create absorptive capacity– this is the ability to manage new information, collaborations and partnerships. Corporations must prepare for new external inputs and enable the company to translate them into successful products and services.

It is about allocating resources to running open innovation projects: Companies often fail to allocate adequate staff, resources and time to open innovation. This prevents them from delivering successful open innovation programs.

It is about creating the capability to integrate external opportunities: External technology, collaborations, and partners all must become a part of your product development pipeline.

It is about adopting an open mindset: Internal information sharing and effective cross-functional team work are essential to create an open culture.

The exact organizational structure and process will vary from organization to organization. In small organizations the approach can be very simple and still be effective. In global multi- nationals the structure tends to be more complex.

Going Forward

In today’s world, it becomes almost imperative for companies to build more collaborations and to expand their own networks. There are four reasons, all priorities, why it makes sense to implement an Open Innovation route with the innovation strategy:

Open the Company’s Horizon

Working only within the company’s existing ecosystem keeps the company in its comfort zone. It is unlikely that major innovation advancement will come from the same players. Identifying early on risks of disruption create new opportunities to reinvent and grow the company’s business. Finding and connecting outside are key for success.

Be Comprehensive

High-performing companies work on multiple fronts to uncover future growth paths. Agility, speed and exhaustiveness are key to opening up unknown channels of science & technology innovation.

Manage Complexity

It is critical to find and connect with most innovative players to cope with the increase of complexity and speed of science & technology developments. Expanding expertise and resources beyond the company’s core knowledge is the best way to secure more collaborations and create impact.

Optimize Resources

Companies tend to focus on finding things and on the open innovation outreach but fail to integrate and capitalize on the opportunities this creates. Corporate innovation is still probably too slow, circling around in known territories, working for the most part with internal and selective networks. Focusing the brightest human resources to increase value where innovative technologies found outside can make an impact on new products, services and operations, therefore on future growth, does seem to be the smart way to go.

Please contact NineSigma if you want to discuss any of the above.

[1] Henry W. Chesbrough (2003), Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology. Harvard Business Review Press, Boston, MA.

[2] Sources: Chesbrough (2003) and Wheelwright, SC, Clark, KB (1992), Revolutionizing Product Development – Quantum Leaps in Speed, Efficiency, and Quality. The Free Press, New York.

[3] Description taken from an article published by Andy Zynga, former CEO of NineSigma. A. Zynga (2013), The Cognitive Bias Keeping Us from Innovating. Harvard Business Review Blog, https://hbr.org/2013/06/the-cognitive-bias-keeping-us-from

[4] In the next 4 sections we use some quotes from Denys Resnick’s chapter on Intellectual Property in Paul Sloane (2011), A Guide to Open Innovation and Crowdsourcing: Advice From Leading Experts. Kogan Page, London. Denys Resnick was executive Vice President at NineSigma.

[5] See https://www.ninesigma.com/case-studies/new-plastics-economy/

[6] Refer for instance to the “CB Insights – State of Innovation Report 2018” accessible from here https://www.cbinsights.com/research-state-of-innovation-report. This report results from a survey of 677 corporate strategy executives.

[7] A. Zynga (2013), Where Open Innovation Stumbles. Harvard Business Review Blog, https://hbr.org/2013/01/where-open-innovation-stumbles

[8] This section draws from a NineSigma White Paper, When to Dive into Open Innovation, written by Stephen Clulow, currently Co-President, Chief Delivery Officer at NineSigma Europe.